On Alum

What is the difference between the various types of alum?

If you have done any natural dyeing or marbling, you have most likely used alum as a mordant. Alum is a metal salt which bonds to both the fiber substrate and the coloring agent, creating an insoluble bridge linking them together. If you are using dyes on fabric or paper, an alum mordant will increase the amount of color that can latch on, and improve the washfastness and lightfastness of the finished piece. Alum is the most commonly used mordant because it is inexpensive, colorless, and toxic only in large doses.

I, like many marblers and dyers, am in the habit of using the term ‘alum’ to refer to two different compounds: potassium aluminum sulfate and aluminum sulfate. These two metallic salts function essentially the same way for mordanting, but it's worthwhile to consider their differences. I will not include aluminum acetate in this discussion, as it is always specified by name and is not in common use for marbling paper.

Potassium Aluminum Sulfate

Historically called potash alum, potassium aluminum sulfate is a translucent white crystalline powder. It is naturally occurring, and has been extracted from alunite in volcanic areas since at least 1500 BC for purifying water, as a styptic, and a mordant. Today it can be refined from bauxite or alunite, or made in a laboratory by adding potassium sulfate to aluminum sulfate. Potash alum is the historical mordant called for in traditional dye and marbling instructions, and in making lake pigments from natural dyes.

Aluminum Sulfate

Aluminum sulfate can be made in a laboratory or refined from various types of stone. In appearance its crystals are jagged, with an opaque white dustiness. Since its introduction as an industrial product in the 19th century, it has replaced potash alum in many applications such as water purification and paper sizing, and is sometimes called papermaker's alum.

What's the difference?

Potash alum and aluminum sulfate may be used interchangeably as a mordant on both cellulose and protein fibers.

Potash alum is more expensive.

Some dyers claim that potash alum gives clearer colors, but I have not noticed any difference between the two. If you have trouble with muddy colors, make sure your alum is from a reputable vendor. Any impurities, such as iron, will sadden your colors.

Most important for practical purposes: Aluminum sulfate is more water-soluble at room temperature. When mordanting paper, most historic manuals call for heating the water before adding potash alum. Heating the water allows potash alum to dissolve quickly.

Alum Quantity for Mordanting Paper

When preparing paper for marbling, it is pre-mordanted with an alum solution.

How much alum to use?

Marbling instructions vary greatly in the strength of the alum solution recommended to mordant paper. I've seen measurements ranging from 1.5 teaspoons to 5 tablespoons per pint of water. How much is enough to make a successful print?

What can go wrong?

If too little alum is used, marbled designs made with watercolor or acrylic paints cannot bond to the paper. Western-style papers used in the European marbling tradition are sized to improve their durability and slow their absorbency. Alum bonded to the surface of mordanted paper is the chemical helping-hand essential for linking marbling pigments to the paper fiber. Any marbler who has accidentally printed on the unmordanted back side of a sheet is familiar with the disappointment of watching their design wash down the drain with the rinse water, having no alum to hold it fast.

However, if too much alum is used, crystals may build up on the surface of the paper without actually adhering to to the paper fibers. In this case, a bit of the excess alum will dissolve into the size as each print is made. If the size becomes polluted with alum, it causes the paint to clump together in a very frustrating way, and must be replaced with fresh size. If you can feel a buildup of powder on the surface of your paper or see white streaks on colored papers, you are using too much alum.

Testing Alum Quantity

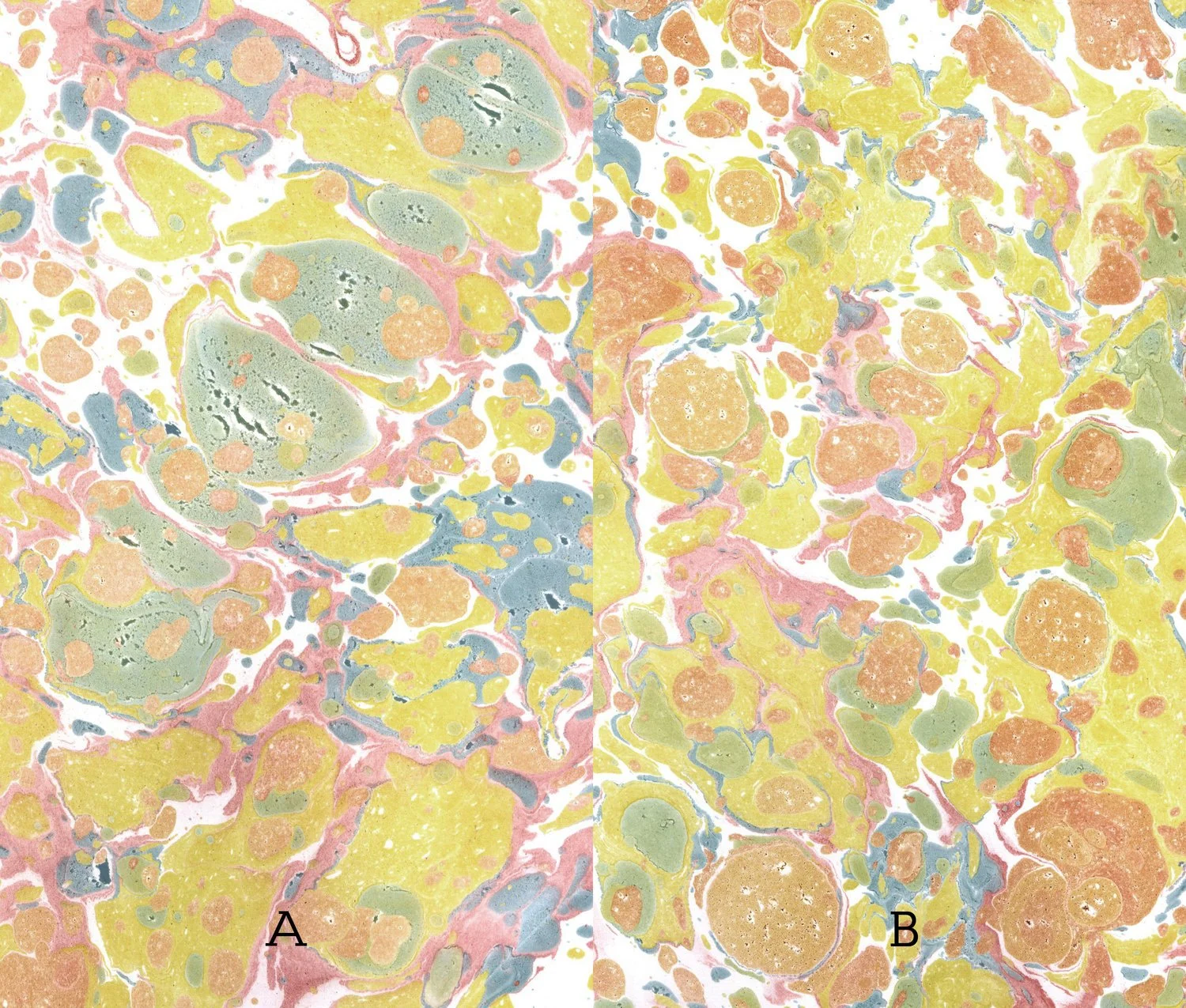

These samples, excepting sample A, were coated with a wash of aluminum sulfate dissolved in warm water:

A no mordant

B 1.5 teaspoons/pint

C 1 tablespoon/pint

D 2 tablespoons/pint

E 3 tablespoons/pint

Unmordanted sample A is comparatively very pale. This was not a surprise, as it has no mordant at all. I was surprised, however, to find no discernible difference the in strength of the colors in samples B-E. I recommendation 1.5 teaspoons (9g) alum per pint water. Aluminum sulfate OR potassium aluminum sulfate may be used.

Alum Quantity for Mordanting Fabric

There are a lot of different recipes for mordanting fabric prior to marbling, but with my natural dyeing experience to guide me, I’d like to share my method. The aim is to evenly apply an alum solution to fabric before marbling, just enough for a permanent print.

Fiber preparation

Firstly, choose an absorbent natural fiber or blend for your fabric. Thoroughly wash the fabric in very hot water with a pH neutral, fragrance-free detergent to remove any starch, sizing, or dirt from its surface - these will impede both the mordant and marbling from being absorbed.

Mordanting by weight

Using a metric baker’s scale, weigh your dry fabric (this can be done before washing).

For plant fibers (cotton, linen, bamboo, ramie, hemp) or fiber blends, measure alum equal to 15% of the weight of your dry fabric.

For animal fibers (silk), measure alum equal to 8% of the weight of your dry fabric.

Fill a clean container with enough warm water for your fabric to swim freely. This can be a bucket, plastic storage container, or your bathtub. Add the alum to the water, stirring until it is completely dissolved. Lower your fabric into the alum solution, swishing it around to release air bubbles. Leave the fabric to soak for 40-60 minutes, stirring every 15 minutes for even absorption.

Empty your mordanting container and fill with fresh water. Rinse your fabric 1-2 times by wafting it through the water to remove excess alum.

Hang the fabric to dry. Mordanted fabric may be stored for up to 6 months before use. Iron with steam before marbling.

The dangers of poor mordanting

I’ve seen recipes calling for as much as 1 1/4 cups alum (20 tablespoons) per gallon of water. That’s a lot. The problem with mixing a very strong mordant solution (following a heavy-handed recipe or failing to follow any recipe whatsoever) may not be immediately evident. But some problems might arise:

Alum is slightly acidic. Over time, that acidity of over-mordanted fabric causes the fibers to become brittle and break apart. If your marbled fabrics feel very dry or brittle, or if they tear during washing or sewing, they may be over-mordanted.

I’ve read that alum ‘eats’ or ‘decomposes’ fabric, and it should never be mordanted more than a few days prior to marbling. This is true only if you over-mordant or use an extremely delicate textile. Following a decent recipe will allow you to mordant fabric months in advance of marbling with no detriment.

Failing to rinse your fabric after mordanting can leave excess alum sitting on the surface. If the un-rinsed fabric dries with any wrinkles, that alum pools in the creases and make a streaky print.

Fabrics that have not been rinsed can deposit excess alum into the size, degrading it over the course of multiple prints. Or worse, your print may bond to the layer of alum sitting on the surface of the fabric, then flake off during rinsing.

Unfortunately fabric that is badly over-mordanted cannot be saved; alum forms permanent bonds and cannot be removed. If you have a batch of fabric exhibiting any of the issues above, best scrap it and start fresh. Small amounts of mordanted natural fiber fabrics (not yet printed) can be torn into thin strips and added to the compost.

Alum and Lake Pigments

Lakes are a class of historical, manmade pigments which include alum in their makeup. In centuries past, marblers utilized lake pigments for their beautiful hues and ease of printing.

What are lake pigments?

Natural dyes (with the exception of vat dyes including indigo) are water soluble. This means they cannot be used for marbling, as they simply dissolve into the size. In order to make these beautiful organic colors (many of which have no counterpart among mineral colors) useful for marbling they must be converted into pigments. A lake pigment is made when dissolved dye is precipitated onto an inert mineral substrate: aluminum hydroxide. This is made from a combination of alum and a neutralizing agent. The lake pigment is filtered, washed, dried, and ground. For marbling it can be mulled with watercolor medium, and used like any other watercolor paint.

Marbling with lake pigments

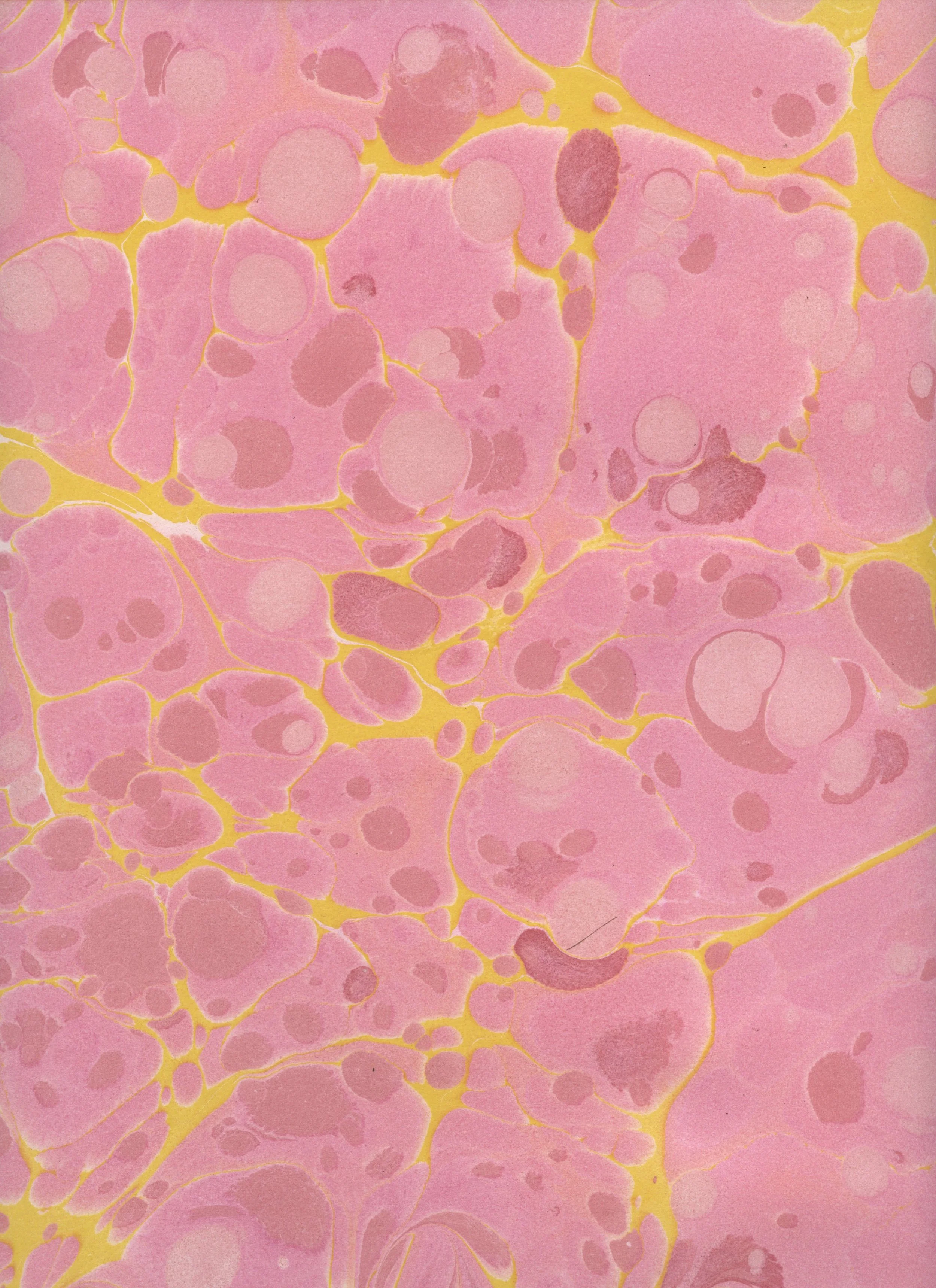

Because lake pigments contain a mordant within them, paper does not need to be pre-mordanted before marbling! I have read this in multiple sources, and the test below confirms it.

A: Unmordanted paper

B: Paper pre-mordanted with 1.5 teaspoons alum/pint water

The mordanted paper absorbs the marbled print a bit more quickly with a slightly sharper quality, but this shows that pre-mordanted paper is not an absolute requirement.

Lake-based watercolors are prepared for marbling just like any other watercolor: each color is thinned to a good consistency and mixed with the appropriate amount of surfactant. You don't need to go through the trouble of grinding your own pigments to enjoy working with lakes, any 'genuine' watercolor lake such as rose madder or carmine will work. It can be difficult to know just what manufacturers put in their paints, and whether they are synthetic pigments simply bearing the names of historical shades, so it's worth seeking high quality paints if you want the real thing.

If you are marbling with a mixture of genuine lakes and other pigments, always pre-mordant your paper.